20 Regression

20.1 Introduction to Regression

So far we have used linear models for analyses between two ‘categorical’ explanatory variables e.g. t-tests. But what about when we have a ‘continuous’ explanatory variable? For that we need to use a regression analysis, luckily this is just another ‘special case’ of the linear model, so we can use the same lm() function we have already been using, and we can interpret the outputs in the same way.

20.2 Linear regression

Much like the t-test we have generating from our linear model, the regression analysis is interpreting the strength of the ‘signal’ (the change in mean values according to the explanatory variable), vs the amount of ‘noise’ (variance around the mean).

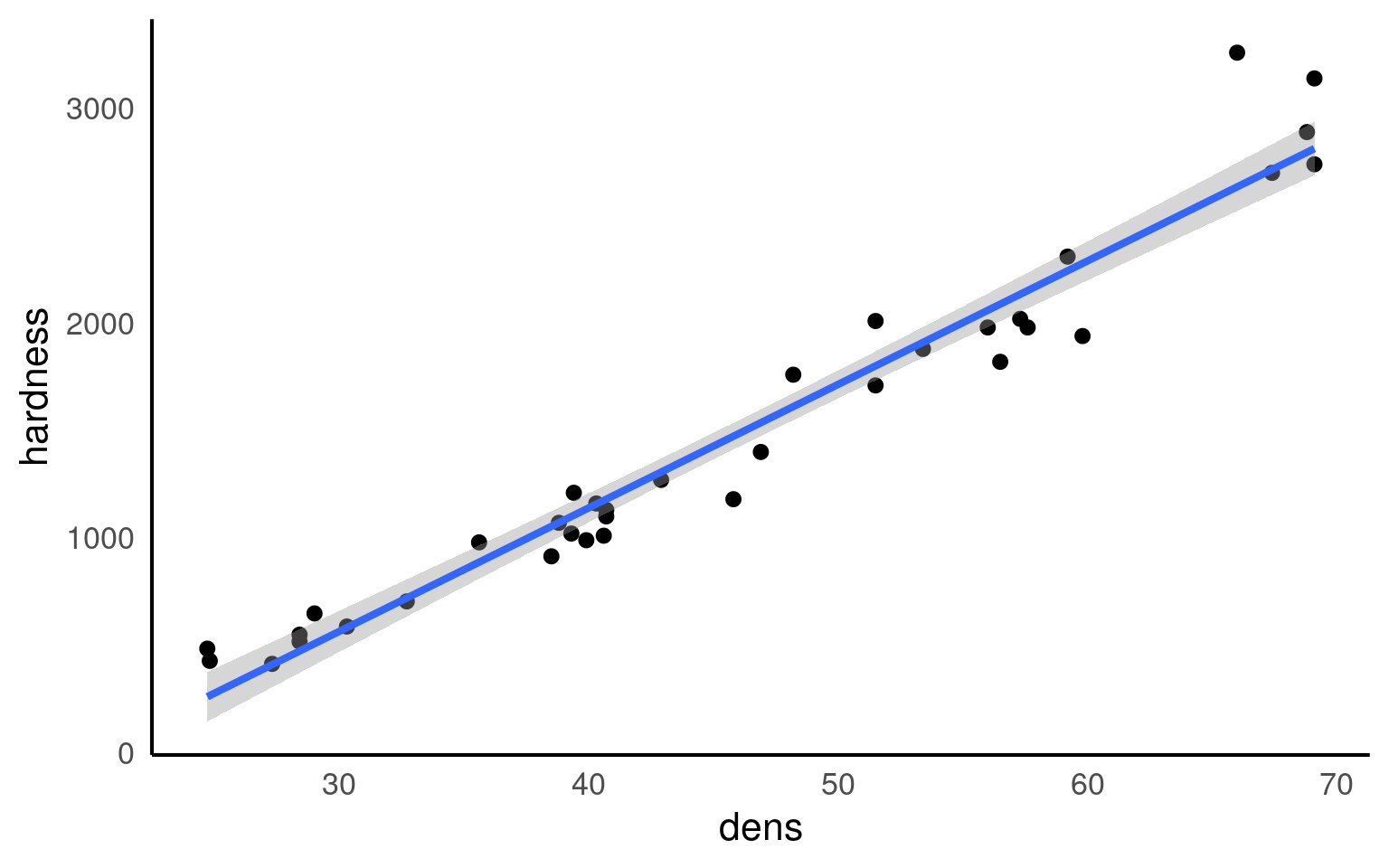

We would normally visualise a regression analysis with a scatter plot, with the explanatory (predictor, independent) variable on the x-axis and the response (dependent) variable on the y-axis. Individual data points are plotted, and we attempt to draw a straight-line relationship throught the cloud of data points. This line is the ‘mean’, and the variability around the mean is captured by calculated standard errors and confidence intervals from the variance.

The equation for the linear regression model is:

\[ y = a + bx \] You may also note this is basically identical to the equation for a straight fit line \(y = mx +c\).

Here:

y is the predicted value of the response variable

a is the regression intercept (the value of y when x = 0)

b is the slope of the regression line

x is the value of the explanatory variable

This formula explains the mean, you would need to include the unexplained residual error as a term to include our measure of uncertainty

\[ y = a + bx + e \]

The regression uses two values to fit a straight line. First we need a starting point, known as the regression intercept. For categorical predictors this is the mean value of y for one of our categories, for a regression this is the mean value of y when x = 0. We then need a gradient (how the value of y changes when the value of x changes). This allows us to draw a regression line.

A linear model analysis estimates the values of the intercept and gradient in order to predict values of y for given values of x.

20.3 Data

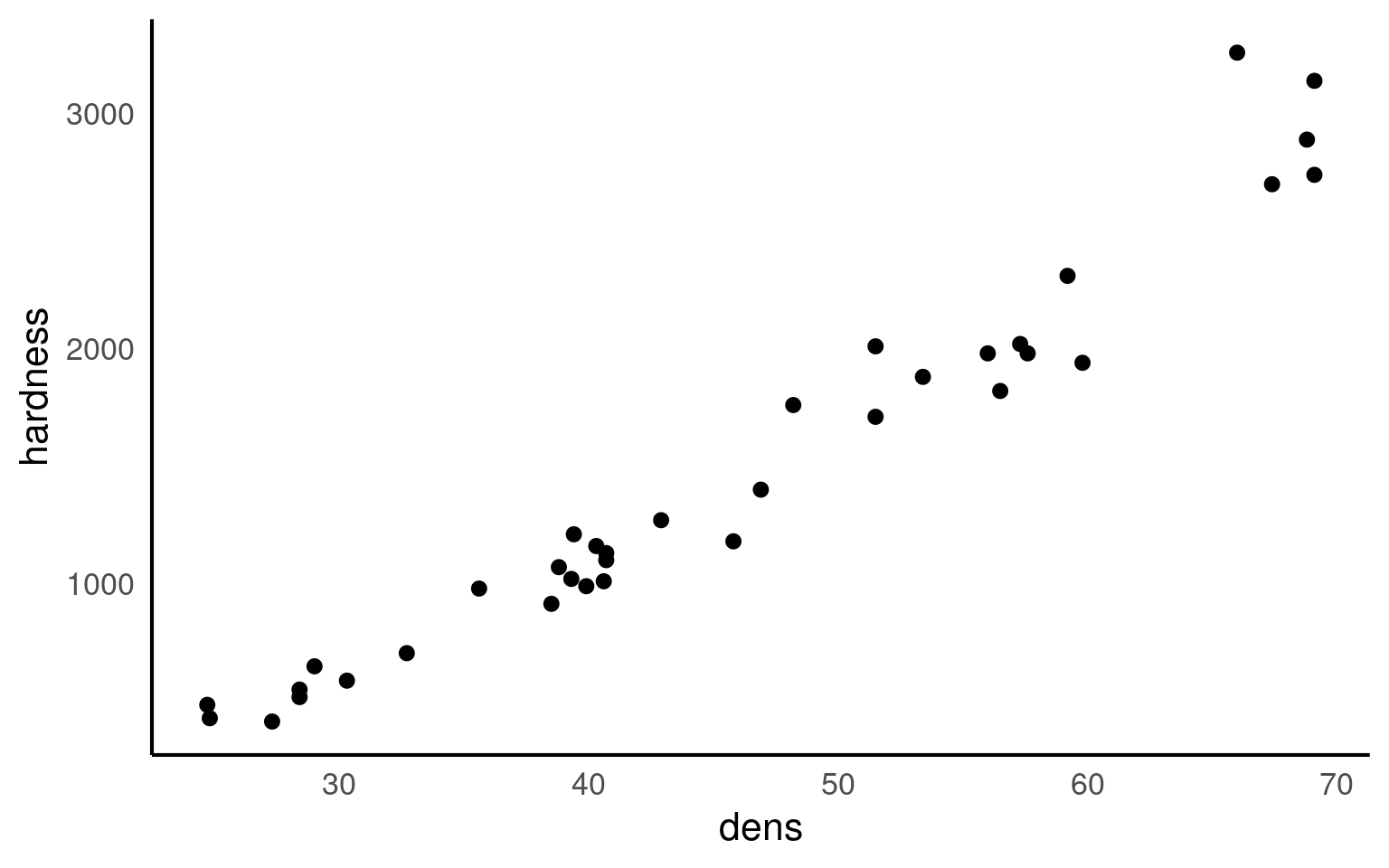

Here we are going to use example data from the Australian forestry industry, recording the density and hardness of 36 samples of wood from different tree species. Wood density is a fundamental property that is relatively easy to measure, timber hardness, is quantified as the ‘the amount of force required to embed a 0.444” steel ball into the wood to half of its diameter’.

With regression, we can test the biological hypothesis that wood density can be used to predict timber hardness, and use this regression to predict timber hardness for new samples of known density.

Timber hardness is quantified using the ‘Janka scale’, and the data we are going to use today comes originally from an R package SemiPar

20.4 Exploratory Analysis & Correlation

Your turn

Wood density and timber hardness appear to be positively related, and the relationship appears to be fairly linear. We can look at a simple strength of this association between dens and hardness using correlation

Hint see Section 16.8

Correlation coefficients range from -1 to 1 for perfectly negative to perfectly positive linear relationships. The relationship here appears to be strongly positive. Correlation looks at the association between two variables, but we want to go further - we are arguing that wood density causes higher values of timber hardness. In order to test that hypothesis we need to go further than correlation and use regression.

20.5 Regression in R

We can fit the regression model in exactly the same way as we fit the linear model for Darwin’s maize data. The only difference is that here our predictor variable is continuous rather than categorical.

This linear model will estimate a ‘line of best fit’ using the method of ‘least squares’ to minimise the error sums of squares (the average distance between the data points and the regression line).

Be careful when ordering variables here:

the left of the ‘tilde’ is the response variable,

on the right is the predictor.

Get them the wrong way round and it will reverse your hypothesis.

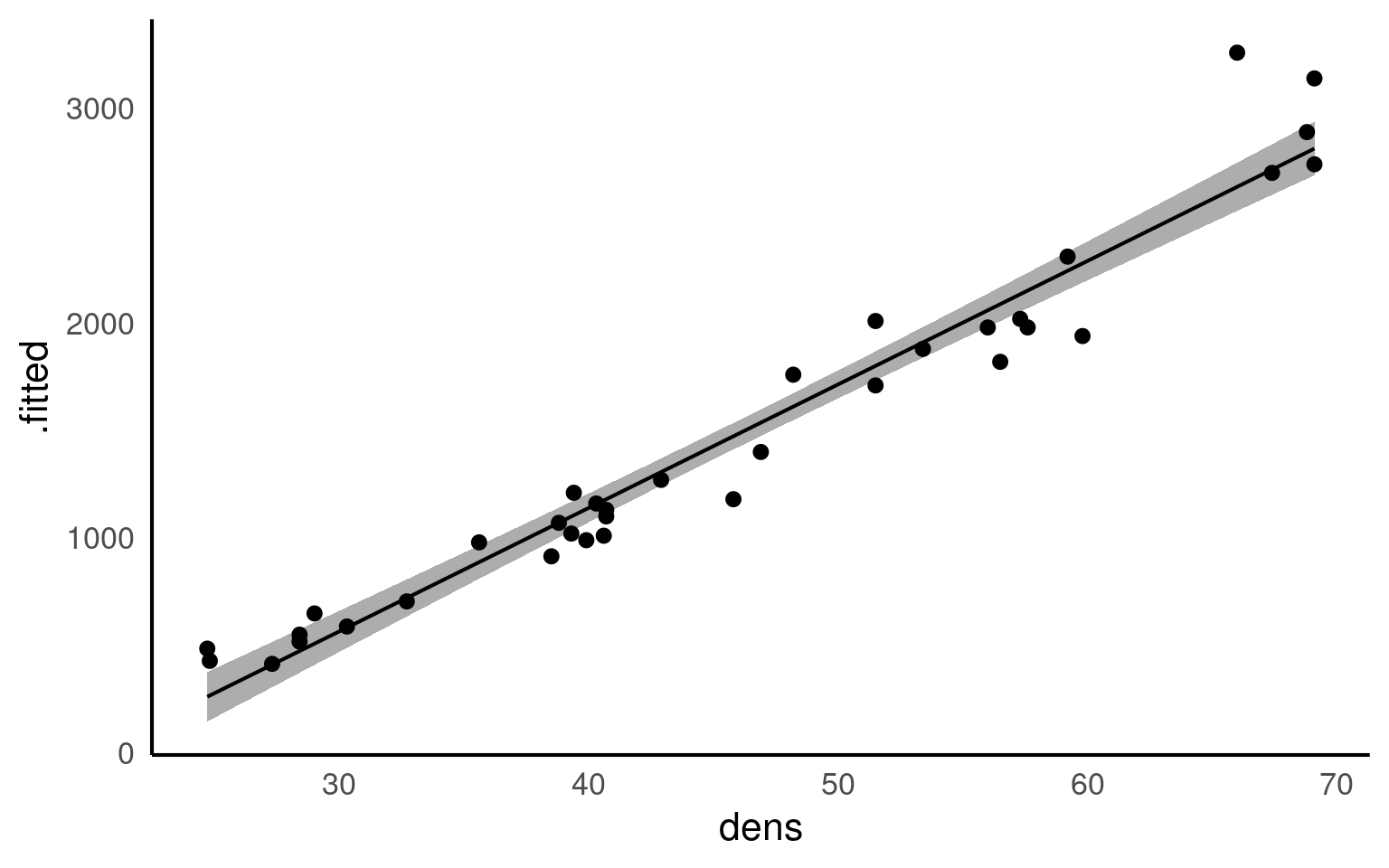

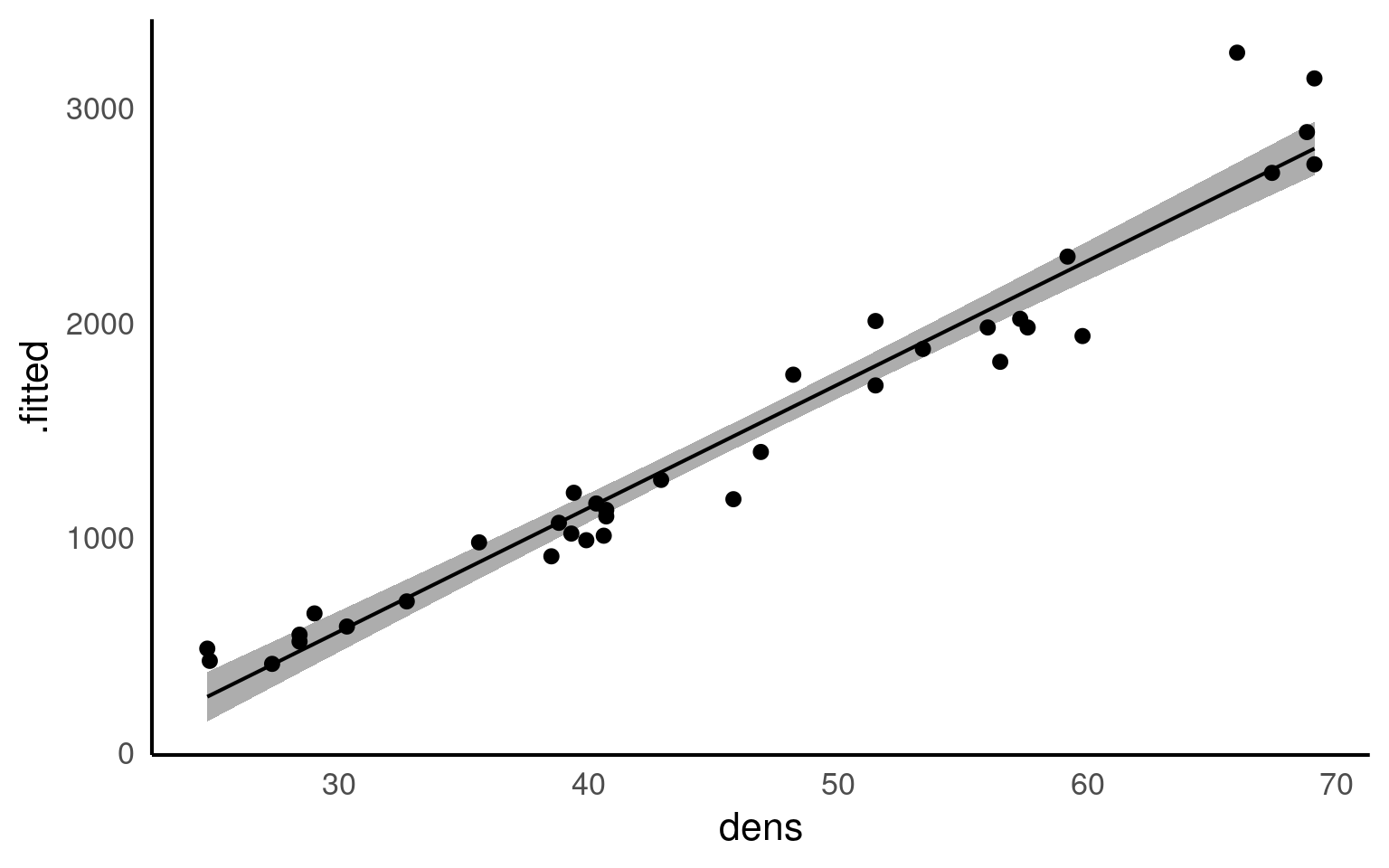

We can add a regression line to our ggplots very easily with the function geom_smooth().

- When we specify the argument

method = lmwe restrict line fitting to an OLS regression

geom_smooth() is a simple way to plot regressions, but it is limited to single predictor models, and should not be used for more complex analyses

20.5.0.1 Summary

Call:

lm(formula = hardness ~ dens, data = janka)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-338.40 -96.98 -15.71 92.71 625.06

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -1160.500 108.580 -10.69 2.07e-12 ***

dens 57.507 2.279 25.24 < 2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 183.1 on 34 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9493, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9478

F-statistic: 637 on 1 and 34 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16This output should look very familiar to you, because it’s the same output produced for the analysis of the maize data. Including a column for the coefficient estimates, standard error, t-statistic and P-value. The first row is the intercept, and the second row is the difference in the mean from the intercept caused by our explanatory variable.

In a test of difference, the intercept represented the mean of one group and the coefficient tells you how much higher or lower the average of one group is compared to another group.

In regression analysis, the intercept is the value when the predictor variable is zero and the coefficient shows how much the response variable changes when the predictor variable increases by one unit, while keeping other predictors constant. This might mean the effect looks small - but it is cumulative.

20.6 Mean-centering

In many ways the intercept makes more intuitive sense in a regression model than a difference model.

Here the intercept describes the value of y (timber hardness) when x (wood density) = 0. The standard error is the standard error of this calculated mean value. The only wrinkle here is that that value of y is an impossible value - timber hardness obviously cannot be a negative value (anti-hardness???). This does not affect the fit of our line, it just means a regression line (being an infinite straight line) can move into impossible value ranges.

One way in which the intercept can be made more valuable is to use a technique known as mean-centering. By subtracting the average (mean) value of x from every data point, the intercept (when x is 0) can effectively be right-shifted into the centre of the data. This is known as mean-centered regression

Your turn

Can you use your data wrangling skills to mean centre the density predictor and produce a more realistic model intercept?

Compare the two models, what is the same and what has changed?

Call:

lm(formula = hardness ~ centered_dens, data = janka_centered)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-338.40 -96.98 -15.71 92.71 625.06

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 1469.472 30.510 48.16 <2e-16 ***

centered_dens 57.507 2.279 25.24 <2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 183.1 on 34 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9493, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9478

F-statistic: 637 on 1 and 34 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16

Call:

lm(formula = hardness ~ dens, data = janka)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-338.40 -96.98 -15.71 92.71 625.06

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -1160.500 108.580 -10.69 2.07e-12 ***

dens 57.507 2.279 25.24 < 2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 183.1 on 34 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9493, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9478

F-statistic: 637 on 1 and 34 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16We should note that our slope of regression and the statistics associated with it are unchanged - that makes sense our relationship is unaltered. Only the starting point for drawing our straight line (the intercept) has moved.

20.6.0.1 Confidence intervals

Just like with the maize data, we can produce upper and lower bounds of confidence intervals:

- What would you say is the minimum effect size (at 95% confidence) of density on the janka scale?

Here we can say that at \(\alpha\) = 0.05 we think the mean change is at least a 52.9 unit increase on the janka scale for every unit increase in density.

Because our 95% confidence intervals do not span 0, we can also say that there is a significant relationship at \(\alpha\) < 0.05.

20.6.1 Effect size

With a regression model, we can also produce a standardised effect size. The estimate and 95% confidence intervals are the amount of change being observed, but just like with the maize data we can produce a standardised measure of how strong the relationship is. This value is represented by \(R^2\) : the proportion of the variation in the data explained by the linear regression analysis.

The value of \(R^2\) can be found in the model summaries as follows

Call:

lm(formula = hardness ~ dens, data = janka)

Residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-338.40 -96.98 -15.71 92.71 625.06

Coefficients:

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) -1160.500 108.580 -10.69 2.07e-12 ***

dens 57.507 2.279 25.24 < 2e-16 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Residual standard error: 183.1 on 34 degrees of freedom

Multiple R-squared: 0.9493, Adjusted R-squared: 0.9478

F-statistic: 637 on 1 and 34 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-1620.7 Prediction

Using the coefficients of the intercept and the slope we can make predictions on new data.

The estimates of the intercept and the slope are:

Now imagine we have a new wood samples with a density of 70, how can we use the equation for a linear regression to predict what the timber hardness for this wood sample should be?

\[ y = a + bx \]

Rather than work out the values manually, we can also use the coefficients of the model directly

Most of the time we are unlikely to want to work out predicted values by hand, instead we can use functions like predict() and broom::augment()

20.7.1 Adding confidence intervals

20.7.1.1 Standard error

20.7.1.2 95% Confidence Intervals

| dens | .fitted | .lower | .upper |

|---|---|---|---|

| 22 | 104.6471 | -21.53544 | 230.8297 |

| 35 | 852.2339 | 772.76915 | 931.6987 |

| 70 | 2864.9675 | 2736.62830 | 2993.3068 |

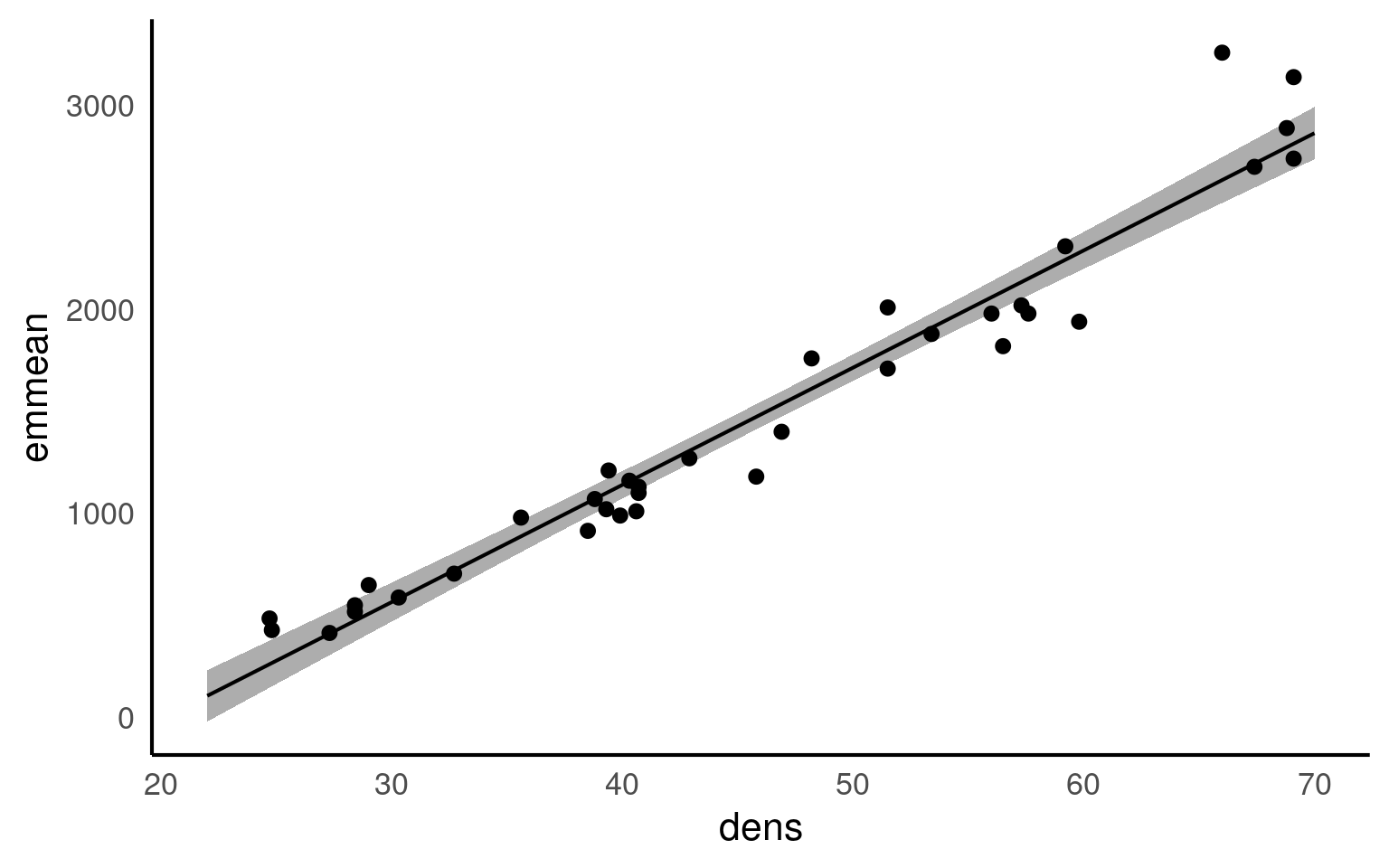

I really like the emmeans::emmeans() function - it is very good for producing quick predictions for categorical data - it can also do this for continuous variables. By default it will produce a single mean-centered prediction. But a list can be provided - it will produce confidence intervals as standard.

dens emmean SE df lower.CL upper.CL

22 105 62.1 34 -21.5 231

23 162 60.1 34 40.0 284

24 220 58.2 34 101.5 338

25 277 56.2 34 162.9 391

26 335 54.3 34 224.2 445

27 392 52.5 34 285.6 499

28 450 50.6 34 346.8 553

29 507 48.8 34 408.0 606

30 565 47.1 34 469.0 660

31 622 45.4 34 530.0 714

32 680 43.7 34 590.9 769

33 737 42.1 34 651.7 823

34 795 40.6 34 712.3 877

35 852 39.1 34 772.8 932

36 910 37.7 34 833.1 986

37 967 36.4 34 893.2 1041

38 1025 35.2 34 953.2 1096

39 1082 34.2 34 1012.9 1152

40 1140 33.2 34 1072.3 1207

41 1197 32.4 34 1131.5 1263

42 1255 31.7 34 1190.4 1319

43 1312 31.1 34 1249.0 1376

44 1370 30.8 34 1307.3 1432

45 1427 30.6 34 1365.2 1489

46 1485 30.5 34 1422.8 1547

47 1542 30.6 34 1480.0 1605

48 1600 30.9 34 1536.9 1663

49 1657 31.4 34 1593.5 1721

50 1715 32.0 34 1649.8 1780

51 1772 32.8 34 1705.7 1839

52 1830 33.7 34 1761.4 1898

53 1887 34.7 34 1816.8 1958

54 1945 35.9 34 1872.0 2018

55 2002 37.1 34 1927.0 2078

56 2060 38.4 34 1981.7 2138

57 2117 39.9 34 2036.3 2198

58 2175 41.4 34 2090.8 2259

59 2232 42.9 34 2145.1 2320

60 2290 44.6 34 2199.3 2381

61 2347 46.3 34 2253.4 2441

62 2405 48.0 34 2307.4 2502

63 2462 49.8 34 2361.2 2564

64 2520 51.6 34 2415.1 2625

65 2577 53.5 34 2468.8 2686

66 2635 55.3 34 2522.5 2747

67 2692 57.3 34 2576.1 2809

68 2750 59.2 34 2629.6 2870

69 2807 61.2 34 2683.2 2932

70 2865 63.2 34 2736.6 2993

Confidence level used: 0.95 20.8 Results

Your turn

Hint - use augment or emmeans to make your predictions and 95%CI - try to add raw data to the plot as well.

Remember if using emmeans it must be converted to a tibble for plotting

We analysed the relationship between wood density and timber hardness on the janka scale with a linear regression model and found that wood density is an excellent predictor of timber harndess (R^2 = 0.95). With an average wood density of 45.7, this produced a timber hardness of 1469 [1407, 1531] (mean [95% CI]) on the janka scale, and for every unit of density, timber hardness increases by 57.5 [52.9, 62.1] (t(34) = 25.24, p <0.001).

20.9 Summary

Linear model analyses can extend beyond testing differences of means in categorical groupings to test relationships with continuous variables. This is known as linear regression, where the relationship between the explanatory variable and response variable are modelled with the equation for a straight line. The intercept is the value of y when x = 0, often this isn’t that useful, and we can use ‘mean-centered’ values if we wish to make the intercept more intuitive. As with all linear models, regression assumes that the unexplained variability around the regression line, is normally distributed and has constant variance.

Once the regression has been fitted it is possible to predict values of y from values of x, the uncertainty around these predictions can be captured with confidence intervals.

20.10 Assumption checking

After conducting a linear model analysis, we often find ourselves with results and inferences. However, before we can fully trust our analysis, it’s essential to check whether the underlying assumptions of the model are adequately met.

Based on these residual checks - what do you think the main issues with the model are?

We begin by fitting a linear regression model to examine the relationship between wood density and timber hardness. The model explains a large proportion of the variance in the outcome (high R squared), indicating a strong predictive association. But there are some minor issues with the model to consider:

Non-linearity: there is a pattern of curvature in the residuals indicating the relationship is not strictly linear

Heteroscedasticty: The residual plots indicate increasing spread of the residuals as fitted values increase - this will affect standard errors, 95%CI and p-values

One observation has high leverage and influences the fitted line

Taken together the diagnostics indicate the model violates some key assumptions underlying linear regression. We might consider nonlinear terms or data transformations - which we can cover later.