4 Data wrangling part one

It may surprise you to learn that scientists actually spend far more time cleaning and preparing their data than they spend actually analysing it. This means completing tasks such as cleaning up bad values, changing the structure of dataframes, reducing the data down to a subset of observations, and producing data summaries.

Many people seem to operate under the assumption that the only option for data cleaning is the painstaking and time-consuming cutting and pasting of data within a spreadsheet program like Excel. We have witnessed students and colleagues waste days, weeks, and even months manually transforming their data in Excel, cutting, copying, and pasting data. Fixing up your data by hand is not only a terrible use of your time, but it is error-prone and not reproducible. Additionally, in this age where we can easily collect massive datasets online, you will not be able to organise, clean, and prepare these by hand.

In short, you will not thrive as a scientist if you do not learn some key data wrangling skills. Although every dataset presents unique challenges, there are some systematic principles you should follow that will make your analyses easier, less error-prone, more efficient, and more reproducible.

In this chapter you will see how data science skills will allow you to efficiently get answers to nearly any question you might want to ask about your data. By learning how to properly make your computer do the hard and boring work for you, you can focus on the bigger issues.

4.1 Load your workspace

You should have a workspace ready to work with the Palmer penguins data.

Load this workspace now.

Think about some basic checks before you start your work today.

4.1.1 Checklist

Are there objects already in your Environment pane? There shouldn't be, if there are use

rm(list=ls())Re-run your script from last time from line 1 to the last line

Check for any warning or error messages

Add the code from today's session to your script as we go

4.2 Activity 1: Change column names

We are going to learn how to organise data using the tidy format2. This is because we are using the tidyverse packages Wickham (2021). This is an opinionated, but highly effective method for generating reproducible analyses with a wide-range of data manipulation tools. Tidy data is an easy format for computers to read.

Here 'tidy' refers to a specific structure that lets us manipulate and visualise data with ease. In a tidy dataset each variable is in one column and each row contains one observation. Each cell of the table/spreadsheet contains the values. One observation you might make about tidy data is it is quite long - it generates a lot of rows of data - you might remember then that tidy data can be referred to as long-format data (as opposed to wide data).

So we know our data is in R, and we know the columns and names have been imported. But we still don't know whether all of our values imported correctly, or whether it captured all the rows.

4.2.1 Open your script from last time and add these new lines at the bottom.

# CHECK DATA----

# check the data

colnames(penguins)

#__________________________----When we run colnames() we get the identities of each column in our dataframe

Study name: an identifier for the year in which sets of observations were made

Region: the area in which the observation was recorded

Island: the specific island where the observation was recorded

Stage: Denotes reproductive stage of the penguin

Individual ID: the unique ID of the individual

Clutch completion: if the study nest observed with a full clutch e.g. 2 eggs

Date egg: the date at which the study nest observed with 1 egg

Culmen length: length of the dorsal ridge of the bird's bill (mm)

Culmen depth: depth of the dorsal ridge of the bird's bill (mm)

Flipper Length: length of bird's flipper (mm)

Body Mass: Bird's mass in (g)

Sex: Denotes the sex of the bird

Delta 15N : the ratio of stable Nitrogen isotopes 15N:14N from blood sample

Delta 13C: the ratio of stable Carbon isotopes 13C:12C from blood sample

4.2.2 Clean column names

Often we might want to change the names of our variables. They might be non-intuitive, or too long. Our data has a couple of issues:

Some of the names contain spaces

Some of the names have capitalised letters

Some of the names contain brackets

This dataframe does not like these so let's correct these quickly. R is case-sensitive and also doesn't like spaces or brackets in variable names

# CLEAN DATA ----

# clean all variable names to snake_case using the clean_names function from the janitor package

# note we are using assign <- to overwrite the old version of penguins with a version that has updated names

# this changes the data in our R workspace but NOT the original csv file

penguins <- janitor::clean_names(penguins) # clean the column names

colnames(penguins) # quickly check the new variable names## [1] "study_name" "sample_number" "species"

## [4] "region" "island" "stage"

## [7] "individual_id" "clutch_completion" "date_egg"

## [10] "culmen_length_mm" "culmen_depth_mm" "flipper_length_mm"

## [13] "body_mass_g" "sex" "delta_15_n_o_oo"

## [16] "delta_13_c_o_oo" "comments"4.2.3 Rename columns (manually)

The clean_names function quickly converts all variable names into snake case. The N and C blood isotope ratio names are still quite long though, so let's clean those with dplyr::rename() where "new_name" = "old_name".

# shorten the variable names for N and C isotope blood samples

penguins <- rename(penguins,

"delta_15n"="delta_15_n_o_oo", # use rename from the dplyr package

"delta_13c"="delta_13_c_o_oo")4.2.4 glimpse: check data format

When we run glimpse() we get several lines of output. The number of observations "rows", the number of variables "columns". Check this against the csv file you have - they should be the same. In the next lines we see variable names and the type of data.

glimpse(penguins)We can see a dataset with 345 rows (including the headers) and 17 variables It also provides information on the type of data in each column

<chr>- means character or text data<dbl>- means numerical data

4.2.5 Rename text values

Sometimes we may want to rename the values in our variables in order to make a shorthand that is easier to follow. This is changing the values in our columns, not the column names.

# use mutate and case_when for a statement that conditionally changes the names of the values in a variable

penguins <- penguins %>%

mutate(species = case_when(species == "Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae)" ~ "Adelie",

species == "Gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua)" ~ "Gentoo",

species == "Chinstrap penguin (Pygoscelis antarctica)" ~ "Chinstrap"))Have you checked that the above code block worked? Inspect your new tibble and check the variables have been renamed as you wanted.

4.3 dplyr verbs

In this section we will be introduced to some of the most commonly used data wrangling functions, these come from the dplyr package (part of the tidyverse). These are functions you are likely to become very familiar with.

| verb | action |

|---|---|

| select() | take a subset of columns |

| filter() | take a subset of rows |

| arrange() | reorder the rows |

| summarise() | reduce raw data to user defined summaries |

| group_by() | group the rows by a specified column |

| mutate() | create a new variable |

4.3.1 Select

If we wanted to create a dataset that only includes certain variables, we can use the select() function from the dplyr package.

For example I might wish to create a simplified dataset that only contains species, sex, flipper_length_mm and body_mass_g.

Run the below code to select only those columns

# DPLYR VERBS ----

select(.data = penguins, # the data object

species, sex, flipper_length_mm, body_mass_g) # the variables you want to selectAlternatively you could tell R the columns you don't want e.g.

select(.data = penguins,

-study_name, -sample_number)Note that select() does not change the original penguins tibble. It spits out the new tibble directly into your console.

If you don't save this new tibble, it won't be stored. If you want to keep it, then you must create a new object.

When you run this new code, you will not see anything in your console, but you will see a new object appear in your Environment pane.

new_penguins <- select(.data = penguins,

species, sex, flipper_length_mm, body_mass_g)4.3.2 Filter

Having previously used select() to select certain variables, we will now use filter() to select only certain rows or observations. For example only Adelie penguins.

We can do this with the equivalence operator ==

filter(.data = new_penguins, species == "Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae)")Filter is quite a complicate function, and uses several differe operators to assess the way in which it should apply a filter.

| Operator | Name |

|---|---|

| A < B | less than |

| A <= B | less than or equal to |

| A > B | greater than |

| A >= B | greater than or equal to |

| A == B | equivalence |

| A != B | not equal |

| A %in% B | in |

If you wanted to select all the Penguin species except Adelies, you use 'not equals'.

filter(.data = new_penguins, species != "Adelie")This is the same as

You can include multiple expressions within filter() and it will pull out only those rows that evaluate to TRUE for all of your conditions.

For example the below code will pull out only those observations of Adelie penguins where flipper length was measured as greater than 190mm.

filter(.data = new_penguins, species == "Adelie", flipper_length_mm > 190)4.3.3 Arrange

The function arrange() sorts the rows in the table according to the columns supplied. For example

arrange(.data = new_penguins, sex)The data is now arranged in alphabetical order by sex. So all of the observations of female penguins are listed before males.

You can also reverse this with desc()

You can also sort by more than one column, what do you think the code below does?

4.3.4 Mutate

Sometimes we need to create a new variable that doesn't exist in our dataset. For example we might want to figure out what the flipper length is when factoring in body mass.

To create new variables we use the function mutate().

Note that as before, if you want to save your new column you must save it as an object. Here we are mutating a new column and attaching it to the new_penguins data oject.

new_penguins <- mutate(.data = new_penguins,

body_mass_kg = body_mass_g/1000)4.4 Pipes

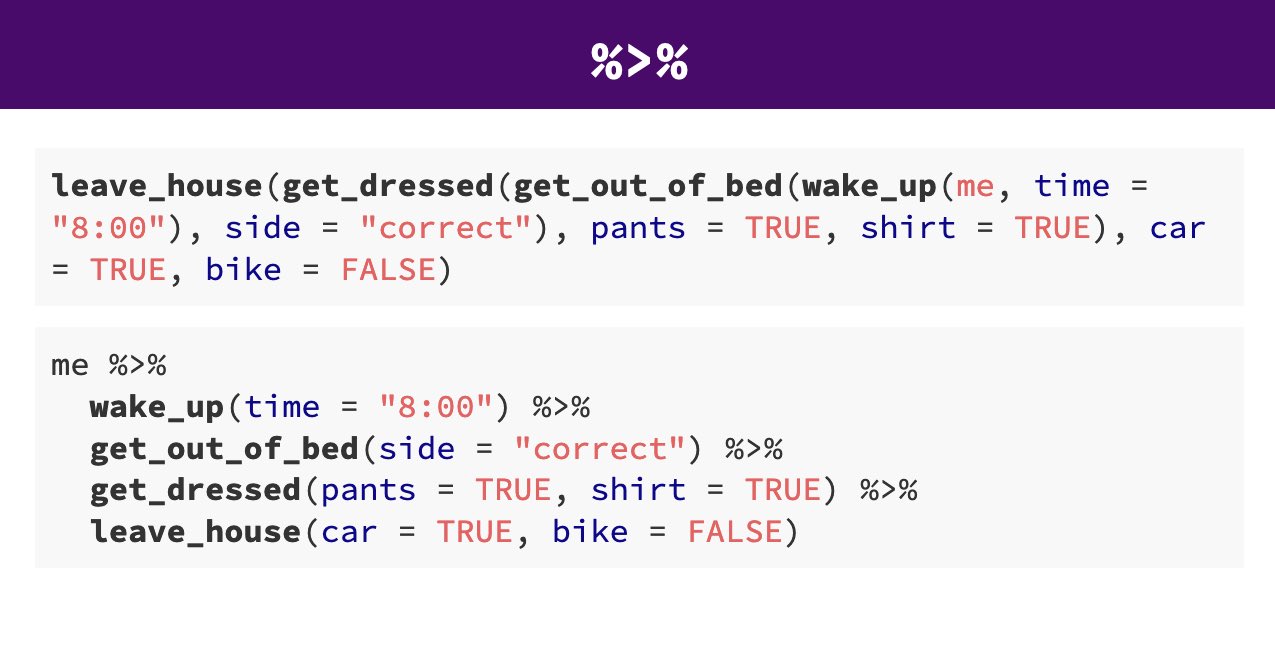

Pipes look like this: %>% Pipes allow you to send the output from one function straight into another function. Specifically, they send the result of the function before %>% to be the first argument of the function after %>%. As usual, it's easier to show, rather than tell so let's look at an example.

# this example uses brackets to nest and order functions

arrange(.data = filter(.data = select(.data = penguins, species, sex, flipper_length_mm), sex == "MALE"), desc(flipper_length_mm))

# this example uses sequential R objects to make the code more readable

object_1 <- select(.data = penguins, species, sex, flipper_length_mm)

object_2 <- filter(.data = object_1, sex == "MALE")

arrange(object_2, desc(flipper_length_mm))

# this example is human readable without intermediate objects

penguins %>%

select(species, sex, flipper_length_mm) %>%

filter(sex == "MALE") %>%

arrange(desc(flipper_length_mm))The reason that this function is called a pipe is because it 'pipes' the data through to the next function. When you wrote the code previously, the first argument of each function was the dataset you wanted to work on. When you use pipes it will automatically take the data from the previous line of code so you don't need to specify it again.

Take the penguins data AND THEN Select only the species, sex and flipper length columns AND THEN Filter to keep only those observations labelled as sex equals male AND THEN Arrange the data from HIGHEST to LOWEST flipper lengths.

From R version 4 onwards there is now a "native pipe" |>

This doesn't require the tidyverse magrittr package or any other packages to load and use.

For this coursebook I have chosen to continue to use the tidyverse pipe %>% for the time being it is likely to be much more familiar in other tutorials, and website usages. The native pipe also behaves "slightly" differently, and this could cause some confusion.

If you want to read about some of the operational differences, this site does a good job of explaining

4.5 A few more handy functions

4.5.1 Check for duplication

It is very easy when inputting data to make mistakes, copy something in twice for example, or if someone did a lot of copy-pasting to assemble a spreadsheet (yikes!). We can check this pretty quickly

# check for duplicate rows in the data

penguins %>%

duplicated() %>% # produces a list of TRUE/FALSE statements for duplicated or not

sum() # sums all the TRUE statements[1] 0Great!

4.5.2 Summarise

We can also explore our data for very obvious typos by checking for implausibly small or large values, this is a simple use of the summarise function.

# use summarise to make calculations

penguins %>%

summarise(min=min(body_mass_g, na.rm=TRUE),

max=max(body_mass_g, na.rm=TRUE))The minimum weight for our penguins is 2.7kg, and the max is 6.3kg - not outrageous. If the min had come out at 27g we might have been suspicious. We will use summarise again to calculate other metrics in the future.

our first data insight, the difference the smallest adult penguin in our dataset is nearly half the size of the largest penguin.

4.5.3 Group By

Many data analysis tasks can be approached using the “split-apply-combine” paradigm: split the data into groups, apply some analysis to each group, and then combine the results. dplyr makes this very easy with the group_by() function. In the summarise example above we were able to find the max-min body mass values for the penguins in our dataset. But what if we wanted to break that down by a grouping such as species of penguin. This is where group_by() comes in.

penguins %>%

group_by(species) %>% # subsequent functions are perform "by group"

summarise(min=min(body_mass_g, na.rm=TRUE),

max=max(body_mass_g, na.rm=TRUE))Now we know a little more about our data, the max weight of our Gentoo penguins is much larger than the other two species. In fact, the minimum weight of a Gentoo penguin is not far off the max weight of the other two species.

4.5.4 Distinct

We can also look for typos by asking R to produce all of the distinct values in a variable. This is more useful for categorical data, where we expect there to be only a few distinct categories

penguins %>%

distinct(sex)Here if someone had mistyped e.g. 'FMALE' it would be obvious. We could do the same thing (and probably should have before we changed the names) for species.

4.6 Summary

# produce a summary of our data

summary(penguins)

#__________________________----This provides a quick breakdown of the max and min for all numeric variables, as well as a list of how many missing observations there are for each one. As we can see there appear to be two missing observations for measurements in body mass, bill lengths, flipper lengths and several more for blood measures. We don't know for sure without inspecting our data further, but it is likely that the two birds are missing multiple measurements, and that several more were measured but didn't have their blood drawn.

We will leave the NA's alone for now, but it's useful to know how many we have.

We've now got a clean & tidy dataset, with a handful of first insights into the data.

4.7 Finished

That was a lot of work! But remember you don't have to remember all of these functions, remember this chapter when you do more data wrangling in the future. Also bookmark the RStudio Cheatsheets Page.

Finally, make sure you have saved the changes made to your script 💾 & make sure your workspace is set not to save objects from the environment between sessions.

We want our script to be our record of work and progress, and not to be confused by a cluttered R Environment.

4.8 Activity: Reorganise this script

Using the link below take the text and copy/paste into a new R script and save this as YYYY_MM_DD_workshop_4_jumbled_script.R

All of the correct lines of code, comments and document markers are present, but not in the correct order. Can you unscramble them to produce a sensible output and a clear document outline?